I don’t claim to be an expert on drawing — I’m not at university for fun — but there is one thing I notice about every person who has ever said “I wish I could draw” and that is that they can, yet something holds them back.

A long time ago, somebody (I sadly don’t remember who) gave me a little bit of advice that I think set me on the course for better drawing. This vague memory of a person – probably leaning over me at a school desk – said “draw what you see, not what you think you see.”

To me, it instantly made sense, I knew what that meant and I’ve tried so many times to pass that on, but every time failed and deemed a patronising snob. I will never be a teacher.

Anyhow, many years later, it’s been enforced again by my favourite man in the world, Angelo DiCinto. He discussed the idea that we have images in our head for words, perhaps more specifically, nouns. It makes sense, right? Ask somebody to draw a house and more often than not you get a square with a triangle on top, maybe a chimney, two windows and a door. The proof that this is in our head is that there is a home button at the top of your browser that looks remarkably like this. It is a recognised symbol.

It’s clear then, we have preconceived images for all the nouns we know. And they come from all kinds of memories and sensory experiences, first hand or even somebody’s illustrations. When we think of an eye, we have all the shapes that make up an eye, and that’s what we draw. In at a close second for most heard sentence regarding drawing, is “I love drawing eyes.” Well I hate to say it but if you love them so much you could try to draw more than a rugby ball containing a football containing a tennis ball, with hair.

I understand why we love drawing eyes but how many times have we drawn an actual eye and not our mind’s eye of an eye? I’m going off my topic… the point is that drawing what we think we see does little to explain what we actually see. And if we want to draw better, we have to observe better. Back to Angelo, then, he says that we must break free from the dictionary, and in the context of life drawing, to not draw the nose how we think the nose should look. Essentially, don’t draw the foot the way you think of a foot in your head or you may as well have a foot in your head.

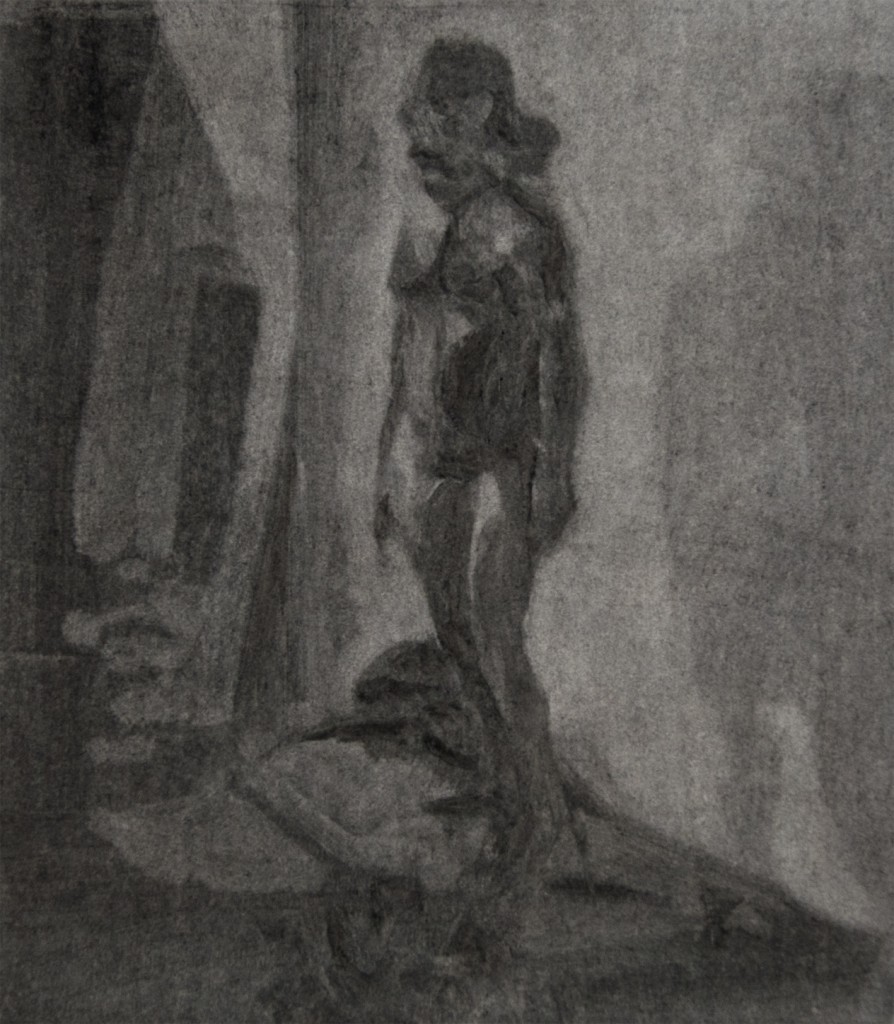

So we let go of our dictionaries and when we see the tone of the board behind our figure to be the same as the tone of his shoulder, there should be no line to distinguish them just because we have a shape of a shoulder in our minds. What we really see is ‘boardshoulder’, and thus it became the title of this piece.